Lecture

Antonino Cardillo

I was born in 1975, as Pink Floyd were recording Shine On You Crazy Diamond. This piece, dedicated to absence, encapsulates a sense of meaninglessness that characterised the 1970s. I begin with this reflection because every life, every experience, is partly shaped by the circumstances in which it takes form. In my case, these circumstances were the 1970s, the city of Trapani in Sicily, and a persistent feeling of estrangement from the place of my birth. It felt as though I did not belong to that context—a sentiment I might describe as a perceived distance between myself and my surroundings.

I referenced Pink Floyd because that album represents an artistic attempt to convey the sensation of dislocation and inadequacy in relation to one’s context. Why do I start with such a personal episode? Because my account is intended to be a parable that transitions from the personal to the collective—or, if you prefer, to the universal. A series of experiences and situations has formed the foundation of my architectural journey, providing guiding principles that have proven to be pivotal.

Purple House

Style

Style asks me: “Who am I?”. The path of architecture that you have chosen to embark on, the pursuit of becoming architects, also involves questioning how special and unique your journey can be. Such uniqueness is closely tied to experiences lived during childhood and adolescence. In my case, this perception of absence led me, during my teenage years, to seek refuge in the world of video games. I spent the first part of my life, up until university, immersed in video games. This detachment, which distanced me from my peers—whom I found boring and even vulgar—led me to disbelieve in reality. It instead opened me to the possibility of imagining stories, educating me to understand that what we call reality is what we perceive through imagination.

I believe this aspect profoundly characterises architecture. Architecture represents the extraordinary ability, which human beings have possessed for millennia, to imagine a possibility. This possibility, even before being physically constructed, takes shape in fantasy. It is an almost magical power, an alteration of physical space through which what we can define as true reality manifests. Unfortunately, we live in a world dominated by the immanent, where consumption and the tangible—linked to economic power and labour—seem to prevail. However, what truly holds power in our lives is the ability to imagine alternatives. This willingness to imagine and believe in alternatives has given rise to the greatest transformations in history. The story of ‘Houses for No One’, mentioned by Professor Biancucci, originates precisely from these considerations. My initial education, strongly influenced by video games and supported by advanced computer skills, led me, as early as the 1990s, to create semi-photographic simulations on the computer. This drove me to challenge the established order, confronting contemporary architecture, which I saw as an expression of a dying capitalism. I worked on the dynamics underlying that power, steeped in historiography, where the recognisability of a figure depends on the interpretation provided by historians and journalists.

I decided to go beyond the figure of the client: there was no commissioner for my work. Instead, I dedicated myself to creating a corpus of works that seemed physically built but were, in fact, a literary invention aimed at constructing a fantastical reality. I began naively sending images that were published in magazines; journalists treated them as realised works. When my ‘Trojan horse’ was embraced by the dominant narrative of architecture, I understood that it could become a form of subversion, even though it generated much criticism. However, that is another part of the story.

A fundamental aspect of this journey emerged when I began studying architecture at this Faculty [now Department]. Unlike previous schools, where I was little interested and bored, I discovered a passion for learning. The decisive encounter was with a special figure: Professor Antonietta Iolanda Lima, who awakened the potential that was dormant within me. For five years, I was her student. After completing history courses, the professor recognised my potential and, through contact with her, the places and stories of her journey, I experienced a sort of time machine. In the 1990s, it was as if I were living the 1960s and 1970s: through Professor Lima and the spaces she designed, the stories she constructed, the scientific research she conducted, her passions, and her struggles.

This experience allowed me to inherit a constellation of meanings that, at least initially, did not belong to me. Through Professor Lima, I learned the scientific method, the historical approach, and the way to enhance my computer and cybernetic skills. More than anything, I understood that history is a perceptual phenomenon that can be written and even modified. This is the power of architecture. Think of Palladio: although he physically constructed works, Palladio is known not for them but for his book The Four Books of Architecture. In this book, the works did not appear as they were actually built, but as Palladio wanted them to be. This ideal, represented in the book, generated an extraordinary historical influence that manifested in England, Russia, and America.

These concepts, derived from historical knowledge, allowed me to overcome the limitations of my native environment, the city of Trapani. Today, we live in a world where pseudo-accessibility and the overabundance of information limit our ability to impact reality. However, altering reality requires historical awareness, which precedes the project. Because the project is the consequence of a philosophical thought that nourishes it.

Another fundamental aspect of the education transmitted to me by Professor Lima was the holistic dimension, a perspective based on the idea of indivisible knowledge, understood as an organic whole. This unified vision was fragmented by positivism and the industrial revolution, events that progressively compartmentalised and professionalised knowledge. In earlier eras, on the contrary, architecture aspired to unify knowledge, translating it into tangible or imagined constructions. The synthesis achieved in an architectural work configures itself as a manifestation of Being, which narrates and expresses itself in a plurality of languages. Through the images of my works that I have shown you, I have tried precisely to restore life to this unifying dimension.

Elogio del Grigio

Form

The most striking aspect of my journey is undoubtedly having subverted an established order, but there is an even deeper element. The message embedded within my works has been interpreted and disseminated in many parts of the world, likely because it has reached a profound dimension belonging to the ‘world of forms’ shared by all human beings. By ‘form,’ I refer to Plato’s eidos, or the idea-form. Architecture, in fact, manifests itself through figures that pre-exist in our imagination.

According to Carl Jung, the Soul has an ancient history: our souls, formed over millions of years, find their manifestation in the realm of imagination. These entities thus transcend our personal history. To better explain myself, consider a daily example: when authenticating on a website, a matrix of nine images often appears with the request to identify an object within it. The robot, unlike us, is unable to easily discern that form because our knowledge is rooted in universals that pre-exist the things of the world (universalia ante rem).

Information technology itself is founded on the awareness of a substantial difference between robots and humans. This growing awareness led me to reconsider the ‘Houses for No One’. As seen in the initial images of the presentation, such houses represented an architecture attempting to establish continuity with Frank Lloyd Wright’s residences, integrating them into a syncretic dimension that embraced elements of the Late Roman Empire, certain aspects of oriental architectures, and modern experiences with reinforced concrete. My goal was to extend these experiences, creating a synthesis that integrated diverse codes.

Later, as I began constructing my first works and delving deeper into the study of analytical psychology, I realised that it became even more intriguing to attempt creating spaces in which ‘presences’ were psychic entities. These entities, in some way, evoked Plato’s eidos.

In recent times, architecture has encountered some conceptual misunderstandings. For example, the early Le Corbusier was associated with a Platonic dimension of form. However, this was a significant misinterpretation. When Le Corbusier stated that “architecture is the play of pure volumes under light”, he was not referring to Plato’s eidos, which cannot be reduced to a mere geometric simplification but rather pertains to a primordial dimension. From a biological point of view, this dimension can be understood as a behavioural schema: something belonging to imagination and revealing itself as a constant in vastly diverse civilisations.

Let us take, for example, passageways or thresholds: elements found in cultures worldwide. For a long time, it was believed that such recurring figures were the result of migrations, but analytical psychology has demonstrated that these forms pre-exist and are the product of millions of years of phylogenetic evolution that have shaped us. Just as the parts of our bodies are the result of this long creative process, so too is our soul—to be understood in a psychological sense, not a religious one—what generates behaviours.

These behaviours form the basis on which architecture can be argued. If architecture manages to access the depths of the soul, it can then reach its highest aspiration: to touch the hearts of people. Its images can transcend the boundaries of architecture itself to become psychological categories, places of dreams, subliminal messages that evoke those infinite experiences lived by Being before the advent of consciousness.

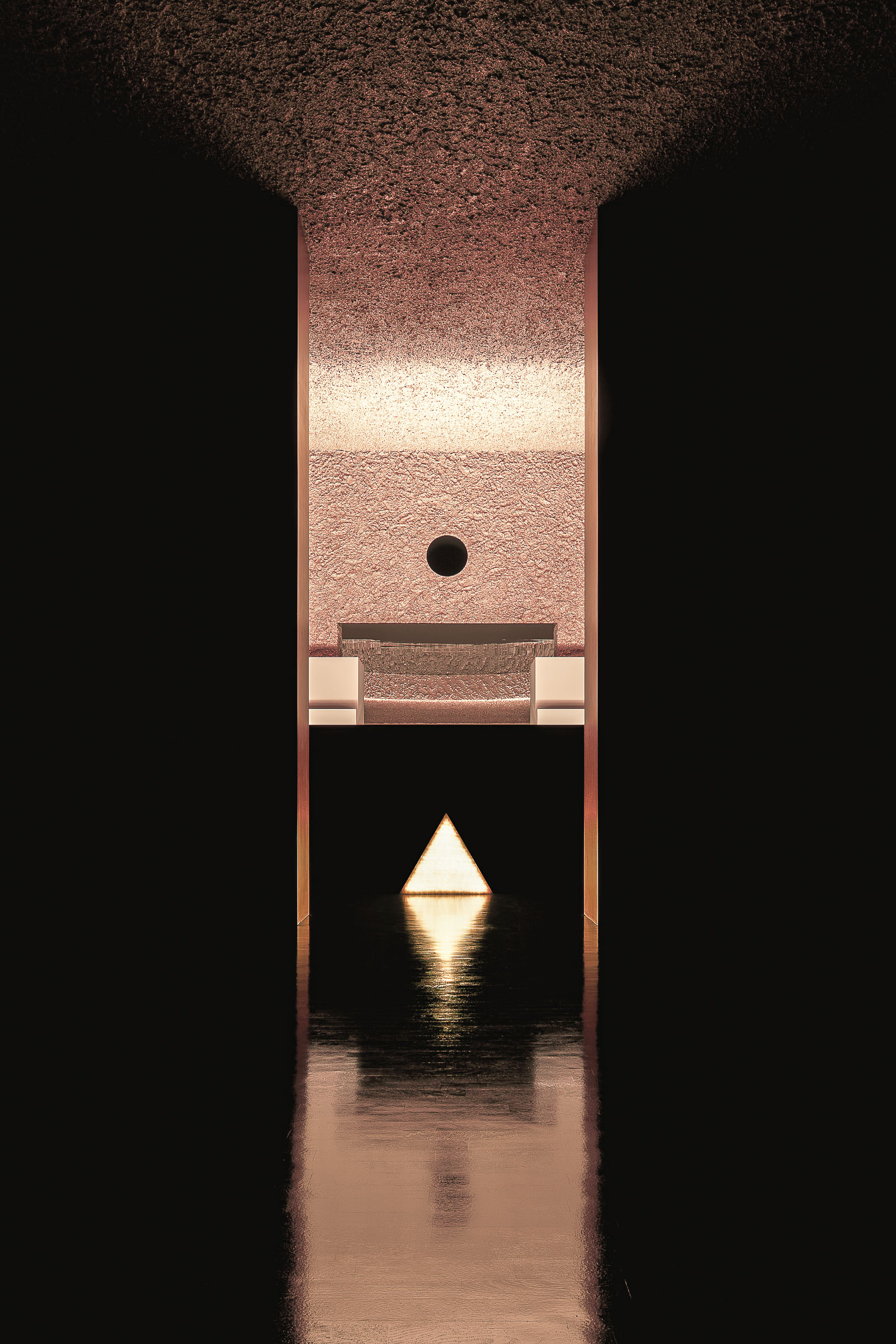

Off Club

Proportion

Proportion represents a significant aspect in the construction of spaces, as demonstrated by the relationship of the golden ratio or the silver section. If, in ancient times, philosophy and mathematics formed an indissoluble unity, modernity has unfortunately led us to consider them as separate disciplines. Mathematics, in particular, has been reduced to a mere tool for measurement and calculation. Yet, according to Carl Jung, numbers are, first and foremost, psychic phenomena.

An emblematic example of this connection can be found in The Sacred Dimension of the Landscape, the seminal book by Antonietta Iolanda Lima. In it, one sees how the unconscious expresses itself through numbers, which become recurring situations capable of reflecting the state of the soul. This aspect has a profound connection to architecture: when we place figures, forms, or ideas in space, we inevitably assign them a quantity. But such a quantity is never arbitrary: it must be a profound narrative. Numerology speaks precisely of this fundamental link from antiquity, a connection particularly evident in Sicily, where the extraordinary heritage of ancient civilisations has endured through time. The remnants of sacred spaces, following numerological principles, are an emblematic example.

This legacy is not limited to sacred spaces but extends also to vernacular architecture, as Professor Lima explained in her book. The archaic dimensions related to numerology have been inherited by popular consciousness, thanks to the unconscious’s ability to transmit meanings that transcend the spirit of the age. The images presented in the section dedicated to proportions illustrate facades that seek to reinterpret the holistic dimension of Renaissance architecture. The latter integrated the complexity of humanity, embracing differences and diversities of knowledge into a single harmonious concretion. The study of the past, therefore, should not be understood as an investigation into something alien to ourselves. Our souls are what connect us, what create a community—distinct from society—where the true deep bond among human beings resides.

This profound connection is what James Hillman describes as Anima Mundi: the soul of the world. The Anima Mundi is an unconscious and subterranean dimension that binds us to the ancient Egyptians, the Renaissance, and every attempt by humanity to understand something of its Being. Architecture, as an expression of this search, has the task of exploring and revealing such connections. However, this cannot happen within the reduction of sociality, where judgments and prejudices prevail. Only by attempting to discover these constants can one access a deeper dimension.

Specus Corallii

Position

The final part of this discussion concerns position. To question position is to ask oneself: “Where am I?”. For an architect, this is a crucial question that must be understood not only spatially but also temporally. We live in a world that imprisons us in a present constructed from the news, where the media tries to convince us that we are entities exclusively tied to this historical period. However, our lives are the result of multiple historicities: an archaic historicity linked to psychological archetypes; a personal historicity that connects us to our ancestors and our recent past; and a historicity of the places we inhabit.

All of this is closely connected to architecture, since our interventions insert themselves into a reality that is not necessarily tangible or built but can also be literary, as I have previously illustrated. Antonietta Iolanda Lima, at a certain point in her career, ceased designing and constructing buildings but continued to create architecture through her writings.

Position, therefore, can be understood as the faculty of employing imagination within the reality of the project’s site, to neutralise the power rooted in violence and abuse that emanates from that place. I too, in my personal experience, have encountered this dynamic. As a recent graduate living in Trapani, I faced few opportunities to emerge. In that context, architecture became a strategy for me to understand how to sabotage the dominant power. This process operates both at the level of personal history and at the level of the history of the places in which we were born.

I believe, therefore, that working in Sicily does not only represent an opportunity arising from the possibility of studying firsthand the built content of the past. From the perspective of collective psychology, this island stands as an extraordinarily complex place, rich in shadows, yet capable of offering profound keys to understanding the nature of Being.

Mammacaura

Notes

- ^ Pink Floyd, Wish You Were Here, Harvest Records, London, 1975.

- ^ Andrea Palladio, The Four Books of Architecture [1570], Dover Publications, New York, 1965.

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung, Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious [1934–54], Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1981.

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung, Psychological Types [1921], Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1971.

- ^ Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture [1923], Dover Publications, New York, 1986.

- ^ Antonietta Iolanda Lima, La Dimensione Sacrale del Paesaggio: Ambiente e Architettura Popolare di Sicilia, Flaccovio Editore, Palermo, 1984.

- ^ James Hillman, The Thought of the Heart and the Soul of the World [1973–82], Spring Publications, Dallas, 1988.