Review

Jana Martin

On July 5 we posted Matt Hussey of The Cool Hunter’s thoughtful piece on the Antonino Cardillo Ellipse 1501 House:

But, […] there comes a time when we’re not quite sure. And if we don’t like it, why are we telling you about it? This new house designed by Antonino Cardillo has stumped us good and proper. Is it just another vacuous interior that looks an awful lot like a museum? Or is it a very shrewd example of how shapes and colors interact when placed next to each other?

At some point Hussey asks, “Where do all the people go?” It’s a great question.

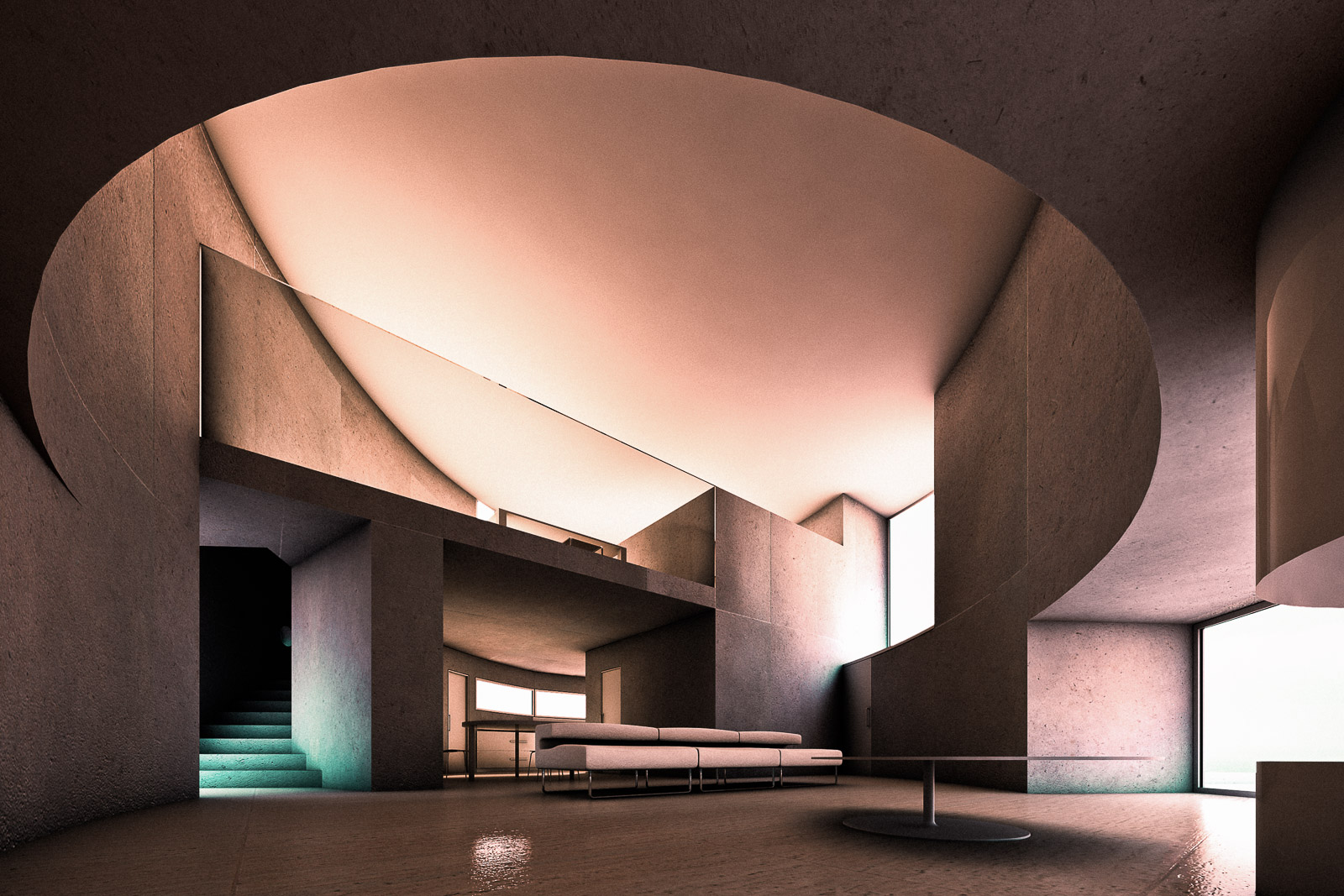

More photos on The Cool Hunter’s post reveal just how ginormous Cardillo’s house is. It appears to breathe: to swell outward and try to escape its own contours. It is a dwelling in which everything is built on a massive scale. The windows are oversized gashes, cut into walls that seem to refuse to accept the interruption.

In this all-concrete interior, with its mass of aggressive, monochromatic curves and volumes, it’s hard to imagine anyone having any more presence than the meek figures used to populate scale models. An irritable but brilliant architectural photographer once quipped to me, “Architecture isn’t for people. Architecture is for architects. The people are just there to provide a sense of scale.”

This was in the late 1980s: we were photographing the PoMo vaingloriousness of a new financial building in midtown Manhattan—for a giant book of glossy photos on buildings in New York (probably to be bought by dwellers of financial buildings). “This building leaves me cold”—the security guard told us as we watched the sun head to its ideal golden spot—“but I like watching the sunset.”

There was the contradiction. The bigger, more ‘blank’ and unornamented the building, the more you tend to pay attention to elements like light. And light is architecture’s dance partner.

Back to the Italian hillside, where this private ellipse house glares out at the shy clutch of pines. “Is it arrogant? Is it vacuous?” Matt asks us. True, you’d have to be sedated or have an ego the size of Trump to be comfortable moving through all that concrete mass and tension. But you could also be an endless daydreamer and be happy here. The view of the sky and the changing light and shadow on the interior are anything but arrogant. Despite the grand thickness, the obvious exercise in math and shape, the building plays with light. It functions as observatory. It makes slides of the moon. It considers the Earth’s place in the universe.

Cardillo, a 32-year-old architect from Sicily, has always played with mass and volume, and I suspect he has always been fascinated with light. His first design was for an aquarium; the fish, one might say, had little to do with it, though water’s refractory qualities must have.

Is this house arrogant? I’d say it could be justifiably accused. You could argue Cardillo is just being Italian, like Berlusconi’s double-breasted suit or the penetrating hood of a Ferrari. Or like a futurist, the original version: the futurists of early 20th-century Italy, with their muscular forms and full-chested energy, are his mass-loving ancestors. Forget the fact (if you remember) that futurism had a certain affinity with fascism. Just think of the aesthetic: as with futurism, there is something very organic, unstatic, dynamic, and male about this house. The house has the swagger of a concrete bull. In the living room area, the ceiling bellies down the span of the room until it narrows into an oblong and penetrates the groove of the window. Certainly that’s intentional, as opposed to ‘meeting’ or ‘intersecting’.

But the futurists rebelled against the concept of a museum, with its cherishing of the fusty past. Such nostalgia they deemed ‘pastism’, meaning an affliction of sentimentality. In that light, Hussey’s question of whether or not the Ellipse House is more a museum than a house is fascinating. This is meant to be a house. And the power of Cardillo’s massive curves here lies in the fact they impose a watchful silence on the interior. The walls overwhelm the space instead of containing it; they don’t define it so much as cancel it out. Standing inside, you have the urge to look out. But the structure is meant to exhibit the sky, to convey a sense of the curvature of the Earth. That’s a global perspective—in a literal sense. Which is not arrogant. What’s arrogant is to not be global.

Antonino Cardillo, Ellipse 1501 House, Rome, 2007.