Review

Ana Araujo

In opposition to mainstream trends in art, design and architecture, usually obsessed with the contemporary and occupied with a continuous reinterpretation, translation, reiteration (and therefore, confirmation) of the now, we find today a curious undercurrent of artists in these fields (amongst which I am myself included) that don’t seem to be at all concerned with reality. Their work may be interpreted as nostalgic, whimsical. Their position (political, social), naïve at best; if not alienated, or disengaged.

It is not the first time in history we witness such an opposition. Around a century or so ago two remarkable women writers cultivated a long-term rivalry over a similar issue. Virginia Woolf, as we know, was then the model of the contemporary (or modern) artist; a woman of her time, a resolute feminist, a person of political and social convictions. Her rival, Vernon Lee, was instead someone who seemed to inhabit the otherworldly dimension of the super-natural: a wanderer in the territory of myths and fairytales. Referring to Lee, Virginia Woolf said “My head spins with Vernon Lee whom I had to review. What a woman! Like a garrulous baby.” Lee didn’t seem to bother much. Accused by her opponents of being a bit of a snob, perhaps she just understood, quietly, that the values she promoted were somehow more profound and real than so-called reality. Intriguingly, her tales remain, today, incredibly relevant, vivid and stimulating. Lee’s art, old-fashioned from the start, doesn’t seem to date.

Timur D’Vatz, Heraldry, 190x235cm, London, 2013.

One hundred and something years on, the work of Russian painter Timur D’Vatz seems to give visual form to some of Lee’s tales. Populated by languorous creatures and fantastic patterns they transport us to a world we know doesn’t exist but that at the same time we feel we belong to. What is this world made of? It is constituted by the wonders of our complex and diverse cultural baggage; a pandemonium of images, memories, stories and histories, disorderly imprinted in our souls (we feel as if they have always been there), and eventually organised—visually, linguistically, spatially, acoustically—by Art (in all its forms). Freud would call this pandemonium our unconscious: the source of our most profound pain and pleasure, the stuff we constantly struggle to make sense of. It was, I believe, in a similar spirit that a controversial German architect from the nineteenth-century, Gottfried Semper, used to argue that the true function of art was not to translate reality but to destroy it; that this was the only way an artwork could be truly fulfilling. “Every artistic creation, every artistic pleasure, presumes a certain carnival spirit, or to express it in a modern way, the haze of carnival candles is the true atmosphere of art. The destruction of reality, of the material, is necessary if form is to emerge as a meaningful symbol, as an autonomous human creation.”

Antonino Cardillo, Crepuscular Green, Mondrian Suite Art Gallery, Rome, 2014. Photography: Antonino Cardillo

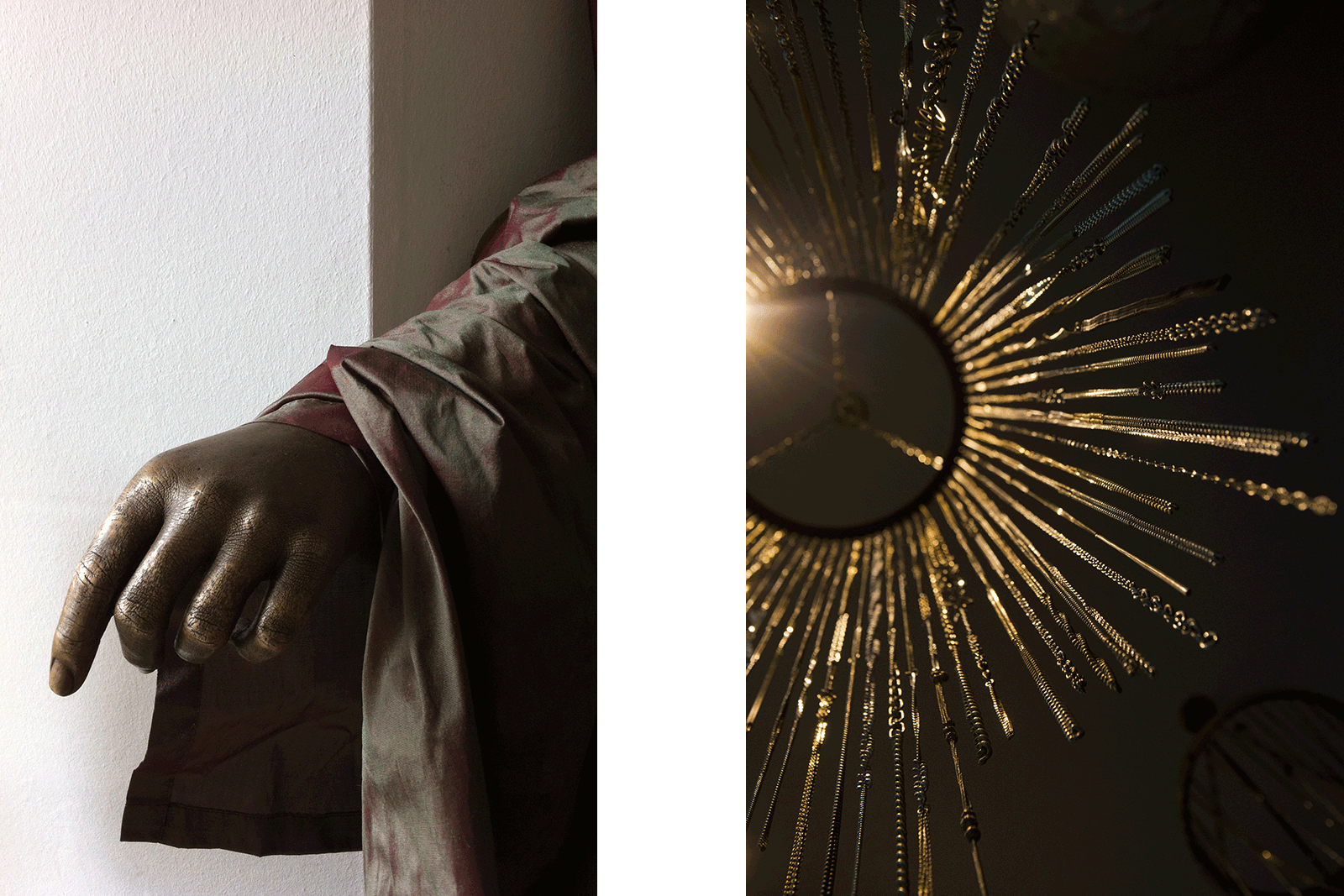

Semper’s carnivalesque spirit pervades the whole oeuvre of Sicilian architect Antonino Cardillo. His Crepuscular Green gallery in Rome evokes the setting of an ancient sacrificial ritual. Egyptian? Greek? Roman? It doesn’t really matter, because once these ancestral images are deposited in our unconscious they are emptied of their historical specificity; as in our dreams, the only link that remains is the emotional one. In a similar guise, Cardillo’s Min sculptures, inspired by the homonymous Egyptian god of fertility, gives shape to what could be regarded as a contemporary image of a talisman; a symbolic magnet, an object imbued with magical properties. Not to mention his most well-known work, House of Dust (also in Rome), an allusion to the religious settings of Duccio and to other masters of the Trecento. A similar process is followed in my two pieces shown here, Rembrandt’s Hand and Ladies of Savoy. Paying tribute, respectively, to the illustrious Dutch artist and to the lives of the remarkable women of the well-known Savoy family, these pieces try to retrieve the emotional density contained in these two cultural moments and to translate it into new spatial artefacts. Rembrandt’s Hand (in collaboration with Willem de Bruijn) responds to the simple brief of refurbishing a domestic living room of a Dutch family based in London. Ladies of Savoy (in collaboration with Roberto Costa) is an ornamental pendant installed in the foyer of a residential block in Belo Horizonte, Brazil—in a building that happens to be named The Savoy Villa.

Ana Araujo, Willem de Bruijn, Rembrandt’s Hand, London, 2013; Ana Araujo, Roberto Costa, Ladies of Savoy, Belo Horizonte, 2014.

Notably, it is not only a process of restoring ancestral and idiosyncratic images (historical, fictional) that defines this type of work. It is also a process of restoring ancestral and equally idiosyncratic techniques and materials. Vatz’s work combines the processes of gilding and stencilling with acrylic and oil painting. Cardillo’s gallery reinvents the Florentine rusticated stone surface in cement (a Roman material) while also making an oblique allusion to the textured ceilings of the Italian Baroque. Rembrandt’s Hand included a laborious bronze cast of the hand of an eleven-year-old girl (the client’s daughter); while Ladies of Savoy combines elaborate handcrafted metalwork with the assemblage of vintage jewellery, accessories, cutlery and crockery. One could say that common to all the works pictured here is an implied assumption that humans are complex creatures who experience diverse temporal and spatial conditions, real and imagined, simultaneously. The Greek philosopher Aristotle used to say that the role of Art is not to portray life as it is but rather to describe how it could be (or how it could have been). Maybe this is, ultimately, what these pieces are trying to do, an idealized reconstruction of the past looking to build a more hopeful future.