Lecture

Antonino Cardillo

Let me tell you my story. Twelve years ago I started building a series of Imaginary Houses. I wanted to communicate my architecture. Thus, I produced seven houses in virtual reality, sending computer-generated images to the most influential architecture magazines on the planet. From 2007 to 2012, more than one hundred and fifty publications, from Australia to California, reproduced these works. For at least six years, many believed the existence of these houses, coming to define a phenomenon of simulated reality. In 2009, the British style and architecture magazine Wallpaper*[1] added a sub-story: I was selected among the thirty best architects of the year. Three years later, the current deputy editor of the German magazine Der Spiegel Susanne Beyer asked for an interview. Beyer came to Rome, we talked for three hours and after a week she published an article titled ‘Impostor’[2] on the magazine editorial. Thus was born the Cardillo scandal, which resonated above all in German-speaking countries.

In that story, I used virtual reality out of necessity. I didn’t bother to ponder a theory. As a writer wants to publish his story, or a director wants to produce his film, I wanted to build my reality. But my position as a young architect did not include commissions that could lead to ambitious works. So I used technology to go, to paraphrase Nietzsche,[3] beyond the fantastic and the real. Destroying the reality and the constituted power, this is the potential that I glimpsed in virtual reality. I tried to do this by interfering with the media, thus engaging a critical subtext in that story.

In 2013, a year after the Der Spiegel article, I built the architectural work House of Dust. House of Dust is an apartment located inside an Umbertino condominium, in a side street of Via Veneto in Rome. The work tells of a bourgeois house that wanted to look like a Renaissance nymphaeum. The artificial grotto, since ancient times, is the place where one gets dirty. The idea was to introduce the dimension of the Dionysian in a bourgeois interior. The idea of the cave belongs to the turbid, the mysterious, the dark desires. The intention of House of Dust was therefore to question the values of cleanliness underlying modern bourgeois architecture. At the same time, the space offers a reading of the owner’s psyche. What inhabits the conscience and what inhabits the unconscious, in the space of House of Dust, is turned upside down.

House of Dust

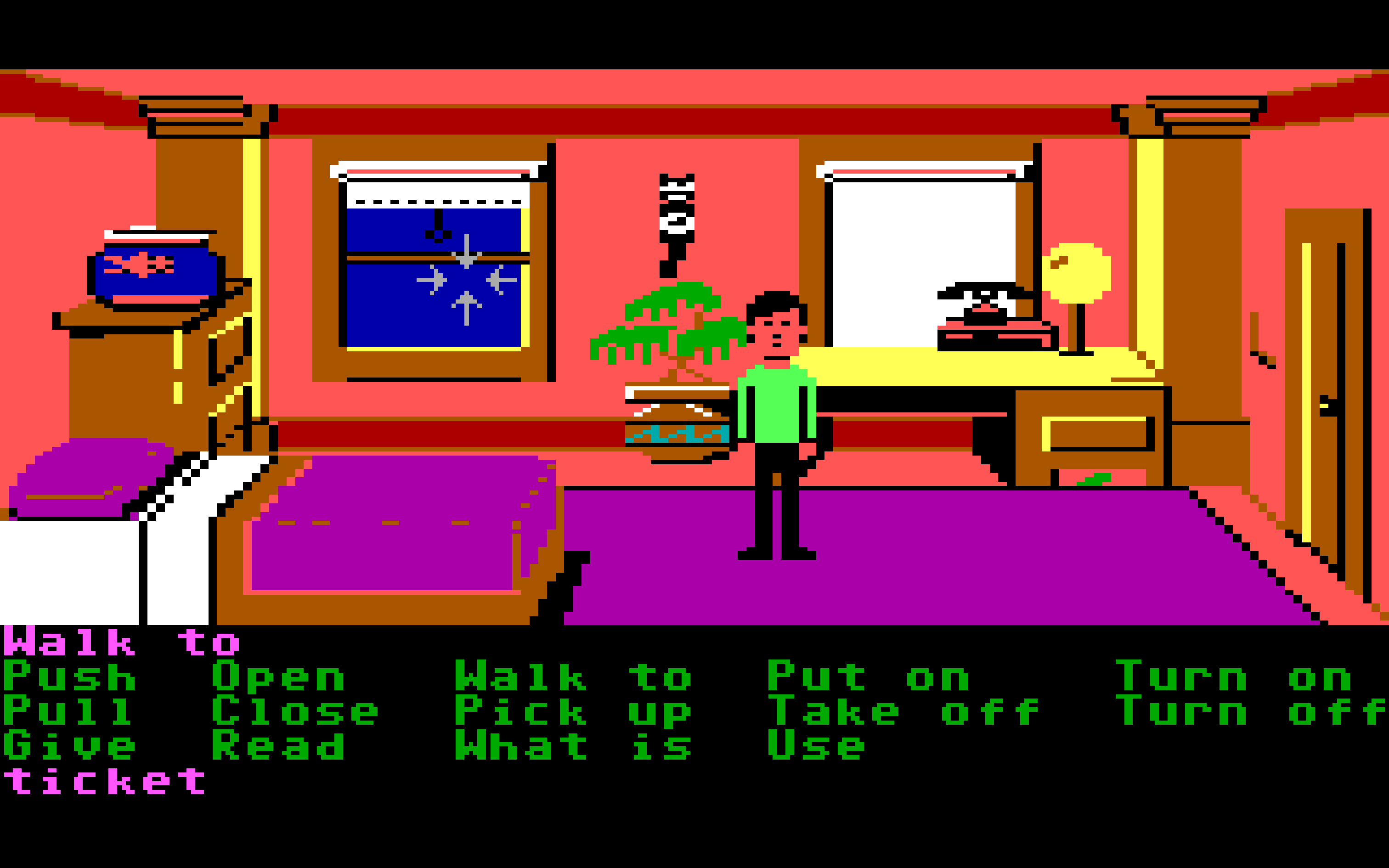

The object of this conversation will therefore be the comparison between this work of architecture and the video game Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders.[4] The analysis that follows is retroactive. At the time of the construction of House of Dust, I had forgotten my gaming experience in 1989. When Diego Grammatico invited me to talk about video games and architecture, the memory of Zak emerged almost immediately. I then put together some screenshots of Zak with photos of House of Dust, and suddenly I realized how much this game had influenced my work. Published in 1988 by Lucasfilm Games, written and directed by David Fox, Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders expanded the narrative and hypertext possibilities of a video game. In Zak, fixed scenes of simplified perspective alternate with two-dimensional scrolling scenes to the left and right. The screenshots we are going to see, compared to what is happening today in the video game industry, appear to be schematic. Despite this, or perhaps because of this, they still teach us something.

Recently, I read The Art of Seeing[5] by Aldous Huxley where the faculty of seeing is broken down into sensation, selection and perception. In the seeing of an adult these passages occur almost simultaneously. In newborns there is sensation, unselected spots of colors. The spots are not yet connected to the entities of the world. Growing up, the selection will focus on some parts of the scene. Finally, the perception, through the interference with the experiences gathered in the memory, will assign meanings.

Zak’s room in the opening scene of the game is composed of a set of color spots. We recognize, in these spots, objects that refer to reality. We recognize a bed, a lamp, a glass ball with red fish and a telephone. If you think about it, it’s incredible! That telephone is not a telephone, just a bunch of pixels. Pixel abstraction stimulates the selection process of colored spots. It promotes a state of attention that reveals the hidden possibilities of narration. You see this missing pixel on the edge of the carpet, underneath, for example, hides a trap door!

Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders

In today’s world of virtual reality, this quality of state of attention seems to have been lost. The obsession for verisimilitude anesthetizes: it excludes the process of synthesis and reduction to the symbol proper to the representation of the human. The fetishism of technology takes over. The stories become secondary, dispersed by the lush computer-generated worlds. Significance and representation divorce and can no longer define a lasting artistic unity.

About ten years ago, during the creation of the series of the Imaginary Houses, using virtual reality in order to make images credible, I had already observed the consequences of this phenomenon. So, when in October 2012 I designed House of Dust, also as a result of the debate followed in the Der Spiegel article, I searched for this same form of simplified representation that today appears to me clarified by my analysis of Zak.

A game like Zak, with its archaic graphics, can therefore be useful to consider and accept this fundamental aspect: as in an inverted sequence, abstraction helps us to recognize that what we perceive is never as it appears to us. What happens is not there, but pre-existing and takes place within us. We are therefore simulators. You who are listening to me, the phenomenon of my voice, happens inside your ears. We already live a simulation of the supposed reality.

The representation of a work is therefore an inseparable part of its existence.

When we see Zak’s room in the opening scene of the game, we might think it’s a simple drawing. I can’t imagine how long it took the designers to achieve this impression of simplicity. I myself researched this sense of simplified perspective in House of Dust. This representative strategy is functional to the emergence of the fundamental elements of narration. In Zak’s room a few patches of color allow us to identify the things of the space: two windows, one open blue and the other white closed, and a purple carpet. The Commodore 64, the computer on which the game was programmed, had only 16 colors. This technical limit, requiring a selection and renunciation effort, enhanced the history of the game.

But let’s look at another image. This is the interior of a shaman’s hut in Zaire, who among other things is also a golfer. How is this hut told? The few colors and pixels available on the Commodore 64 made photographic digitization of materials almost impossible. Thus, the idea of the straw floor becomes an alternation of purple and yellow lines, and the idea of textile architecture, typical of the tent-hut, becomes a mesh decoration on the upper part of the walls of the room. Even House of Dust presents a texture on the upper part of the walls that evokes the fundamental narrative of the work: the idea of the cave. The texture, therefore, in both cases becomes narrative.

At one point in the game, two female students turn their bus into a spaceship and find themselves near a hostel on Mars. Nearby, pyramids and a mysterious Face on Mars constitute an abandoned alien building complex. Inside the building-face, which turns out to be an alien temple, we find three revolving walls cashed in deep recesses, with pedestal devices at the side with a sphere on three feet. The main photograph of House of Dust proposes the same set of things: a deep recess with a passage-secret wall at the bottom, which here does not lead to the labyrinth but rather in the kitchen, and some tripod tables, one with a sphere.

Through my story, I hope I have shown how Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders possesses a power. The power to bring out the submerged potentials of each of us. When I played Zak I was fourteen. I lived in Trapani, Sicily, and I felt lonely. I had no friends, my friends were the authors of Zak in San Francisco, but I understood that now. I played a reality conceived and built by someone who lived on the other side of the planet. I didn’t read books, my parents didn’t have a library. This game, and a few others, were an invitation to destroy that reality. They indicated a possibility: to believe in another story. Believing in the possibility of going beyond the fantastic and the real. This division does not exist, it is only a construction of our time, which wants the imagination confined to art galleries and museums.

Antonino Cardillo, Da Zak McKracken a House of Dust, paper presented to the Rome Video Game Lab 2019, Istituto Luce Cinecittà, Theatre 11, Rome, 2019. Photography: Danilo Balducci

Notes

- ^ Tony Chambers, Jonathan Bell, Ellie Stathaki, ‘Architects directory 2009’, Wallpaper*, no. 125, eic. Tony Chambers, London, Aug. 2009, pp. 74, 76‑77, 81.

- ^ Susanne Beyer, ‘Hochstapler: Römische Ruinen’, Der Spiegel, no. 27/12, Hamburg, 2 July 2012, pp. 3, 121‑123.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse. Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Zukunft, C.G. Naumann, Leipzig, 1886.

- ^ David Fox, with Matthew Alan Kane, Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders [videogame], Lucasfilm, San Francisco, 1988.

- ^ Aldous Huxley, The Art of Seeing, Harper and Row, New York, 1942.