Article

Antonino Cardillo

History must be handled with care, says Antonino Cardillo, who warns that too much respect for the past is smothering the potential of Italian architecture.

The history of man has developed through continuous interaction between different cultures. It often happens that the dominant take possession of the submissive, managing to disguise the process by carefully rewriting history. This has probably resulted in the belief on the part of some societies that they are the exclusive owners of something. Would the late medieval artistic and scientific flourishing in northern and central Italy, strongly stimulated by the influx of Sicilian poets and intellectuals from the court of Federico II of Svevia, which later matured into humanism, have been the same without the pillaging of Eastern culture that took place during the crusades?

And taking a closer look, seven centuries before the Protestant Reformation, hadn’t the Muslims already abolished the religious hierarchy and saints? And still, what was the art of late Roman empire if not an extraordinary melting pot of architects, artists, philosophers and politicians originating from the most remote provinces of the Empire? It is well known, for example, that barrel vaults, a distinctive feature of Roman architecture, were imported from Persia. So, why do some think it is scandalous to see before them a building in Rome by an American architect, a building in Florence by a Japanese architect or a building in Venice by a Spanish architect?

In 1959 Reyner Banham in an illuminating article about the Italian retreat from modern architecture (The Architectural Review, no. 125, pp. 230‑235) warned that “the recent work of Gae Aulenti, Gregotti, Meneghetti, Stoppino, Gambetti, and their associates and followers and the continuing controversy supported by Aldo Rossi and others in their defence has created a crisis in the whole status of the modern movement in Italy.”

In September 2005, 35 professors, some of great intellect, appealed to the president of the republic denouncing “the risk… that interrupts the continuity of research begun in the 1930s [in Italy]… carried on with the innovative spirit of many representatives of successive generations.”

This generation of architects has experienced a period in which their architecture was mainly commissioned by the state. The same happened in France, but there, young architects, such as Rogers and Piano, gave new vitality to Paris. In Italy, everything happened in an oppressive environment, born of a collusion between the universities and the political establishment.

Consequently, the private sector has not been a decisive experimental field and few architects have been interested in research to provide residential buildings of good quality. This is definitely a missed opportunity for the fabric of our cities.

History teaches us that architecture generates place. Today the historic complexity of Italian cities is compromised by a tragic void of contemporaneity. Many administrators and architects believe they are respecting the past, replicating its forms and colours, transforming it into an abstract category in which critical conscience sleeps. But we need to ask yet again: the specific locations of a place, their so-called ‘traditions’, have they always been immune to geographical influences, to external pressures?

Our times are the culmination of a continual historic and geographical process. Censuring its existence negates history itself. In the past 10 years the ‘modern’ has been reinstated by fashion, design, interiors, cinema and music. It has become the dominant aesthetic category, undergoing at the same time a continuous erosion of meaning.

Cannibalising it substitutes modern myths for antique ones, but the process remains false. The improper use of a very recent period risks altering the meaning of the original, creating a parallel and more acceptable history. Many people are stimulated by signs of a recent past and, not having the means to historicise them, reduce them to abstract icons, idealised and interchangeable.

Have we codified new languages or are we taking signs, places and objects from recent history and continually re-elaborating them? Is this a new form of historicism?

Architecture, from my point of view, is the art of building spatial events dislocated from time and changing in the light. An opera, for example, can only be understood through the paths and the journeys that someone undertakes when experiencing its entirety. Some people only look to the melody for a correct analysis of the opera. However, the melody itself tells us nothing about where and how it was placed inside a conceptual sequence.

In recent decades the spread of architecture by print media has unfortunately stimulated, even in the most interesting architectural studies, the production of photogenic buildings, which, when visited, reveal themselves as ephemeral, incapable of going beyond the enthusiasm of the moment to reach that timeless state that distinguishes the great architecture of history.

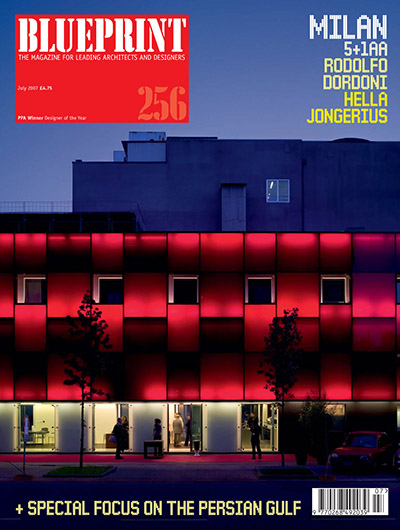

The page 58 of the 256 Blueprint issue.