Lecture

Antonino Cardillo

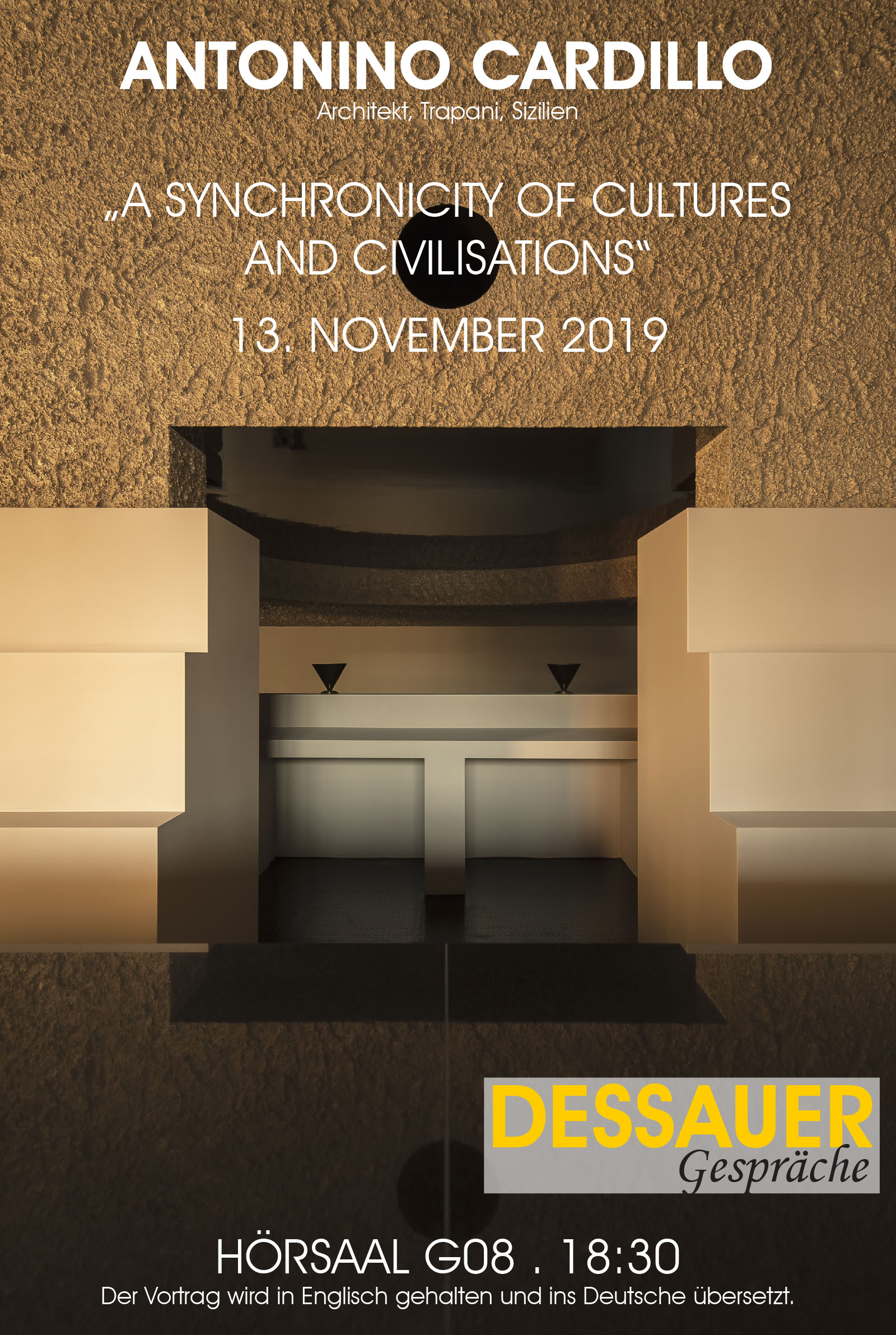

This conference is on the theme of creative process consciousness. Consciousness almost never emerges the moment the work is created, but only afterwards.[1] I believe that this is relevant for the development of a code that is not the only consequence of the circumstances. The representation of the work has always been a fundamental aspect of my discourse on architecture. I will then present seven images of my projects, all of which I have photographed myself. These works explore the idea of a sacred universe, where cultures and civilisations, ancient and recent, come together in singularities that tell of how the Psyche has diversified and projected its contents in the different eras and different places of the world. A few days ago, I assigned titles to these images, which propose interpretations of each work.

The reflection in the river

The title of this first image may seem wrong because the usual preposition ‘on’ has been replaced by ‘in’. But this slip of the tongue could reveal something relevant to architecture. Architecture is a type of perception of reality and the topic perception refers to psychology and philosophy. As a young man, I was often concerned about the phenomenon of reflection. I wondered: if reflection happens in perspective, and therefore does not occupy an a priori position in space, does it exist only in each of our personal visions? Following on to this thought, could the reflexivity of a pavement, which is not just a physical property, perhaps reveal something else to us? Look at this image: it is the entrance to the architectural work Specus Corallii (Latin locution of ‘coral cave’), built in Trapani two years ago. It represents two elongated arch passages leading to a green seabed, perhaps a reference to the Islamic mihrab. ‘In’ the floor, a reflection happens that reveals the presence of a light whose source is hidden. This state of affairs could relate to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave that says: you can try to see that something whose source you are not yet able to understand only through its reflection.[2]

Specus Corallii

The cave and things

The reference to Plato’s allegory continues in the next image, which portrays the architectural work House of Dust located in Rome, near the Villa Borghese. Here the cave refers to the objects. Plato’s allegory depicts people reduced to chains for having mistaken for reality shadows cast on the cave wall by a magical fire coming from their shoulders.[3] They live in the illusion that those shadows are reality and this may well be a valid metaphor for what is happening in our present time: people live in the illusion of objects—where objects are also people, social groups, and other components of our physical life—and at the same time objects gain power over people. Thus, objects become a subjectivation of our perception. We are under the illusion that they are our reality. Thus, this image could reveal a parody of our condition today. In it the space is portrayed as a small theatre or dollhouse, inside which there is a collection of objects: an elongated arch, a pink glass handle, a sofa upholstered in raw wool, a marble table on three feet, a white sphere on a green lacquered coffee table on three feet, a green lamp hanging from the ceiling, a cut of floor light, a Japanese chair from the 1970s. My approach is therefore ambiguous: at the same time it depicts aesthetically and underlies criticalities.

House of Dust

The guardians of gold

This image represents the Crepuscular Green architectural work located in Rome. It refers to the opening scene of the Rheingold, part of Richard Wagner’s four-day drama Der Ring that includes much content from the mythology of the peoples of northern Europe. In that scene of a dawn immersed in the Rhine, gold represents the idea of primordial nature.[4] In this room, the upper walls and ceiling look like a cave of green gold. The arched altar surmounted by two black trumpets evokes the memory of a bridge over a river. Behind, there is a walled door, also covered with gold. In the opening scene of Rheingold, the reins of the Rhine protect the treasure of nature; it exists beyond good and evil, beyond the boundaries of the human. Through this scene Wagner unveiled to the moderns the surprising mythological meanings that wrap around the golden ring, which today’s common sense wants representative of marital fidelity: gold, in the state of nature, is free, protected by the handmaids of the Rhine. But the desire denied by the handmaids to the dwarf Alberich, leads to the curse of love that bends gold into a ring. And that ring, the fruit of cursed love, gives its possessor a unique power over the world.[5] The idea staged by Wagner is that love and power are a pair of opposites. And for power, love is cursed. This paradigm concerns the state of the discipline of architecture today, which manifests itself as an ordinary consequence of business successes. But the spirit of architecture comes from the soul. It reveals distant meanings to us, lost in the past or in possible futures, outside the present time. Thus, the Guardians of Gold protect this path that leads to the door of essence. In the time we live in, gold appears to be linked to wealth and success, but for the alchemists of Middle Age Europe, gold represented a metaphor for the final stage of a spiritual process: the search for the philosopher’s stone. This process offers us a multitude of obscure and highly metaphorical literature, which by modern observers has often been considered bizarre or even meaningless. But in the first half of the twentieth century, Carl Gustav Jung’s Psychology and Alchemy book proposed that such non-logical contents could represent an unconscious projection of those psychological functions repressed by the Christian society of that era.[6]

Crepuscular Green

The sacred eroticism of the phallus

This image represents the Min sculpture, designed for a temporary exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. To the north-west of Rome, the Etruscan tombs of Cerveteri conceal, under large domes of earth, burial rooms with carved tombstones. On their surfaces the forms of the sex of the inhumate are recurrent: an elongated arch for men, a triangular tympanum for women. This element will become, later, the basic vocabulary of Roman architecture, often reunified in the aedicule. Arches and tympani, therefore, could have come down to us not for the validity of use (structure), but as lasting anthropomorphic signs. What we know about the things of architecture is derived from the endless manipulations and prejudices of the millennia. Fragments of content are often encountered that suggest that eroticism, then repressed during the history of civilisation, may have been a possible origin of the sacred.

Min at the Soane

The place of the nymph

This image portrays the project Colour as a Narrative for the Illuminum perfumery located in London in the ward of Mayfair. It continues the investigation of the Primordial Images. In capitalist society, fragrances are sold as trademarks. The rules of lettering rule. But fragrances are elusive and invisible entities that relate to sensory function. Thus, resurrecting the state of nature in central London, this twenty-seven square metre space stimulates the senses through the tactile quality of its coarse walls. In the centre, a hemicycle of thirty-seven glass vases contains drops of different fragrances. The place of the nymph, thus predisposing to olfactory perception, evokes mythological experiences and the alchemical laboratory: each vessel acts as a spell.

Colour as a Narrative

The temenos of the psyche

This image represents the main hall of the Specus Corallii project in Trapani, of which the first image of the conference sequence showed the entrance. Trapani is my hometown and the place where I have chosen to live today. This arched peninsula, in the past, was a harbour of Eryx. In the ancient Mediterranean, Eryx was known for an archaic cult whose name we no longer know. Its female adepts were on a par with erotic officiants and priestesses.[7] Eroticism and sacred thus formed a unity and had not yet been differentiated. The cult was so pervasive that it survived until the Middle Ages. Subsequently, he was repressed and syncretised by a Marian cult that sublimated the erotic past of the place with the arrival of a painting from the sea.[8] I have always been fascinated by this story that could be akin to that of the Mount of Venus (Venusberg) of Richard Wagner’s drama Tannhäuser. The cult of Eryx was probably celebrated within a sacred precinct. The sacred precinct is a constant presence of the past. Temenos for the Greeks and Pairidaēza for the Persians to whom the Semitic idea of Paradise refers. Thus, the main hall of the Specus Corallii project features a precinct adjusted in plan by a rectangle in silver section 1+√2. In elevation, it appears to be divided into two parts by an imaginary horizon line. The part below evokes the imagination of the monuments of ancient civilisations (state of civilisation). The one above, the erotic act of the masonry trowel on the wall (state of nature). For Carl Gustav Jung, the temenos is a magical circle in which the unconscious can be encountered and where unconscious contents can be brought to the light of consciousness.[9] Thus, this space reverses the common order of the parts: what is conventionally below is above, and what is above is below, proposing an enantiodromia.

Specus Corallii

The symbols of transformation

This last image depicts the Japanese-Italian restaurant and bar project Off Club in Rome. Here I tried to combine some recurring elements in my previous projects all together in one code, where different contents come together in a symbolic space. The symbol is often confused with a graphic sign by modern Westerners. But the symbol is much more: The Symbols of Transformation is a seminal book by Carl Gustav Jung. The book was initially called The Symbols of Libido, with reference to Freud’s psychoanalysis. But over the years, Jung’s studies led to the discovery of the idea of a collective unconscious, an argument initially rejected by Sigmund Freud. This caused the relationship with Sigmund Freud to break down.[10] By substance of things, this conflict might recall the story of the Bauhaus (see Johannes Itten and Walter Gropius). According to Plato, the hyper-uranium of ideas and forms is prior to the things in the world. Or, following Carl Jung’s empirical approach, primordial images or archetypes could be a consequence of the history of the origin of consciousness, of that million-year-old phylogeny that still inhabits our collective unconscious. In accordance with Analytical Psychology, this architectural project tries to give voice to the so-called ‘shadow’ of the soul. As with an apotropaic magic, the representation subtracts energy from the corresponding psychic content, previously projected onto the object.[11] Modern architecture often proposes ideal visions of a common good; plans of utopia in which it seems that evil does not exist or has been definitively eradicated. But evil, deprived of its representation and integration with reality, returns with virulence following unpredictable paths, manifesting itself in life through compulsive and unconscious collective and individual actions.

Off Club

Culture, civilisation, synchronicity

After the presentation of these seven interpretations of my works, I can now introduce the main topic of the lesson: why cultures and civilisations? The English language, and the French from which it derives, seem today to give the word culture almost the same meaning as that of civilisation. This does not happen in the Italian and German languages. I find this linguistic change interesting enough to understand the prevailing English perspective of the world we are still living in today. According to Thomas Mann,[12] the word culture refers to those irregular and controversial phenomena well presented by many mythological stories. They appear to be acting against the law and are often perceived as a dangerous threat to civil society. On the contrary, civilisation refers to the phenomenon of a positive society, which expresses itself through a shared order and law. Both phenomena form a pair of recurrent opposites in the stories of men, such as the conflict between Medea and Jason. Carl Gustav Jung proposed that a possible balance between culture and civilisation can be the main way to achieve self-awareness.[13] We are currently living in a time when civilisation has taken over. Our civilised environment constantly represses our deepest instincts. Our urbanised environment, both in the physical and digital space, is short of culture. And here we need clarification: unlike the common and revised use of the word, the cultural phenomenon is not the experience of the museum or the concert (which are once again phenomena of civilisation). I try to explain with an example: the radical life of Richard Wagner was a cultural phenomenon; but his dramas represented today in the theatre, are a phenomenon of civilisation.

Through the seven images presented here, I tried to collect in a singular time many problematic meanings of the past, trying to recompose parts of our Psyche dispersed and fragmented by the utilitarianism of modern times. The ultimate goal of my work as a designer is therefore to stimulate the intuitive function, trying to reflect on the architecture the unknown background of our soul.

Notes

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung, ‘On the Nature of the Psyche’ [1947/1954], Collected Works, vol. 8, Princeton University Press, 1969, p. 231.

- ^ Plato, Republic, book VII, c. 375 BC, 516a.

- ^ Ibid., 514a.

- ^ Richard Wagner, Der Ring des Nibelungen [1869], vol. 2, tr. Franco Serpa, Teatro alla Scala, Milan, 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Ibid., p. 16.

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung, Psychology and Alchemy [1944], Princeton University Press, 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Vincenzo Adragna, Erice, Coppola Editore, Trapani, 1986, pp. 10‑11.

- ^ Ibid., p. 27.

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung, 1980, op. cit., pp. 63, 177.

- ^ Sigmund Freud, Carl Gustav Jung, The Freud/Jung Letters [1906–1913], Routledge & K. P., London, 1974, 330J, pp. 525‑527.

- ^ Op. cit., Carl Gustav Jung, Psychology and Religion [1938–1940], Collected Works, vol. 11, Routledge, London, 1970.

- ^ Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man [1918], Frederick Unger Publishing Company, New York, 1983, pp. 35‑46.

- ^ Carl Gustav Jung, Psychological Types [1921], Collected Works, vol. 8, Routledge, London, 1971, p. 309.